An overview of European eID solutions that allow citizens to perform transactions with public authorities – related to examples of implementations at the country level

by Ioana Bour, UL, ID Management Center

With the development of eGovernment services, it became handy for citizens to be able to prove their identity online. By doing so, they have access to online accounts associated with their real-life identity, from where they can conduct various transactions with public authorities and possibly also with private parties. Europe shows a great diversity of electronic identity (in short: eID) implementations, varying from the traditional username-password combinations to the more sophisticated smart card solutions.

With the development of eGovernment services, it became handy for citizens to be able to prove their identity online. By doing so, they have access to online accounts associated with their real-life identity, from where they can conduct various transactions with public authorities and possibly also with private parties. Europe shows a great diversity of electronic identity (in short: eID) implementations, varying from the traditional username-password combinations to the more sophisticated smart card solutions.

In order to prove her identity for certain – especially governmental – services in the online environment, a user needs to prove she is in possession of certain information or token that links her natural identity to an online account. This is called authentication; it is usually preceded by identification with a valid ID card/ passport etc. to the authority issuing the eID credential.

Online authentication implies user’s possession of valid credentials (e.g. username-password, certificates etc.), which are issued either by the Government or by Trusted Third Parties. Further on, after being authenticated on a website or portal, the user may find it useful to be able to make statements or sign contracts in a way that is legally binding. It was for this purpose that electronic signatures needed to be developed. Similar to real life, the electronic signature must not only contain information about the signatory, but also be trustworthy. Being able to authenticate and to electronically sign documents while connected to the internet is what builds up the concept of electronic identity.

The eID scheme of a country can support multiple systems. In short, online authentication can be achieved by using password-based solutions, Public Key Infrastructures and Attribute-based Credentials. Signing can be performed by using the first two aforementioned systems only.

Password-based systems

Password-based systems are those schemes that allow the users to authenticate and to electronically ‘sign’ a document or an action (that is, to agree with the contents of the document 1/8 or to the action being performed) by entering their username and password. The passwords are either static (one password for every log-in) or dynamic (e.g. One Time Passwords – OTP), which allows the further classification of these systems in username-password combinations, OTP lists, OTP received via SMS or generated via OTP tokens.

Password-based systems are those schemes that allow the users to authenticate and to electronically ‘sign’ a document or an action (that is, to agree with the contents of the document 1/8 or to the action being performed) by entering their username and password. The passwords are either static (one password for every log-in) or dynamic (e.g. One Time Passwords – OTP), which allows the further classification of these systems in username-password combinations, OTP lists, OTP received via SMS or generated via OTP tokens.

PKI

Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) is a set of hardware, software, policies, and procedures needed in order to manage a public-key cryptographic system. Asymmetric or public-key cryptography is based on the use of two different keys for encrypting and decrypting data: one which is publicly- made available (“public key”) and another, which is kept secret (“private key”). The public key is linked to the identity of the individual through a certificate, a document that is (digitally) signed by a Trusted Third Party, such as a Country’s Certification Authority. This is what the authentication server actually receives in order to read the public key of the user. The hierarchy and the management of certificates containing the users’ public keys are the basis of the Public Key Infrastructure. PKI eID solutions can be further divided based on their implementation into soft certificates, implementations on smart cards, on the mobile SIM card or on other tokens.

ABC

Attribute Based Credentials solutions (ABC) are types of systems in which the information about the user is stored in entities called ‘attributes’. Multiple attributes construct a credential which is provided to the user by an Issuing Authority. During a transaction with a service provider, a user’s attributes give information about the rights the user has, without giving information about the user’s identity. For this reason, they are also called ‘Privacy Preserving Credentials.’

Trends in European eID

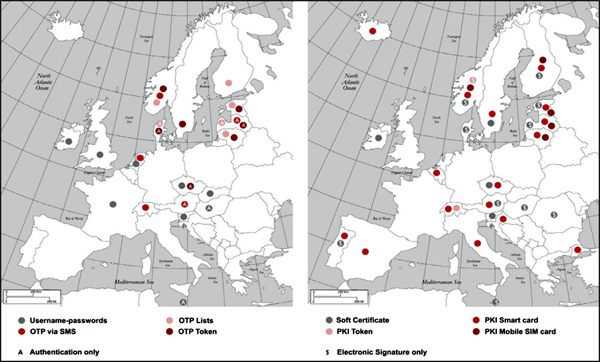

Out of the 31 countries being studied for both Authentication and Electronic Signature schemes dedicated to citizens, 17 of them deploy password-based solutions, 26 have implemented Public Key Infrastructures and one uses an Attribute Based Credentials solution. Seven European countries (the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Lithuania, Norway and Sweden) give their citizens the choice between a passwords-based solution and a PKI implementation.

The figure below gives a per-country overview of the various solutions that exist in Europe. At first glance, one can observe that a multitude of solutions exists in the Nord ic and Baltic countries, for both password-based systems and PKIs. The uniqueness of this region is that the Governments have established effective collaborations with banks and mobile network operators. The majority of the password-based systems used here are OTPs for logging into the online banking environment (the banks being the identity providers for the solution called BankID ).

Only in two Nordic countries – Denmark and Norway – eID solutions based on OTPs are initiated by the public authorities. The successful Nordic cooperation can also be observed in the case of Mobile Public Key Infrastructures: the Mobile PKI solution was introduced by private parties: telecom companies in Finland and Latvia and banks together with telecom companies in Norway, Sweden (where a mobile version of the BankID was developed) and Lithuania. The only exception is Estonia, where the success of the national eID card encouraged the Government to introduce its mobile version (Mobiil-ID).

In the rest of Europe, there are certain clusters of countries that tend to adopt similar eID schemes. One such cluster is UK – Ireland – France, formed by countries that lack sophisticated eID solutions; they allow their citizens to declare their taxes online after authenticating themselves with username and password. Username-password combinations are also used in the Netherlands, for both authentication and digital signing. Users can authenticate on Government and Third Parties portals and ‘sign’ (that is, agree with a piece of information of document) by entering their password again. Citizens can choose between static passwords or OTPs via SMS.

Although not highly secure, the Netherland’s DigID is a successful solution – it is being used not only in relation with the Government, but also in the education sector (e.g. enrolling for a new academic year), by health insurers, for logging in on their websites etc. Several companies adopted a combination of password-based system and soft certificates. This is the case of Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovenia and Malta, where citizens authenticate on Governmental portals with username-password combinations and use a Public Key Infrastructure with soft certificates for signing electronic documents. In Latvia – although it is allowed to authenticate by using an OTP token provided by banks, the same method cannot be employed for signing – this action needs to be performed by using either a PKI soft certificates or PKI smart cards (the national eID card or the eSignature card).

In the period 1999-2006, Finland (1999), Estonia (2002), Italy (2002), Belgium (2004), Spain (2006) and Portugal (2006) implemented the eID functionality on the national ID cards. The solutions employ classic Public Key Infrastructures, with two different key pairs and certificates for authentication and digital signature, respectively. From the countries listed above, Estonia, Belgium, Spain and Portugal show satisfying adoption rates – influenced mainly by the mandatory character of the cards and by the multitude of services citizens have access to.

Although Finland was the first European country to actually implement a PKI on national cards, these were never mandatory and Finnish citizens were better used to other authentication / digital signing mechanisms (e.g. bank OTP), which remained in use even after the introduction of the PKI FINeID card. The same applies to Italy. A new wave of PKI cards is prepared to be launched in Central and Eastern Europe in the near future: Bulgaria, Greece, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Russia are all having discussions and making preparations for national eID cards. Latvia and the Czech Republic already introduced PKI smart cards in 2012.

In Austria and Iceland eIDs are not implemented on national ID cards. The main PKI cards are here bank cards which are Secure Signature Creation Devices (SSCD); In Austria, every citizen can apply for an eID and activate it on bank cards, professional cards, public officials’ service cards etc., while in Iceland, the certificates attest the membership of an individual to an organization / company and can be activated only on bank cards.

There are also cases of specially issued cards bearing the eID functionality only, issued both by public authorities (in Sweden – TaxCard, in Italy – National Services Card, in Latvia – eSignature card) and private parties (in Switzerland – cards issued by three different parties, in Norway – the BuyPass card). In Germany, the Government introduced an Attribute- based Credentials smart card in 2010, which guarantees the user’s privacy and control regarding what data is sent by the chip.

Several factors influence the adoption of new eID solutions, either catalysing or hindering the process. These are: the number of services being built around the eID solution, its ease of use and perceived usefulness, the availability of other eID solutions, switching costs and perceived security and privacy threats.

Availability of services

The availability of services to be accessed via the eID solution influences positively the adoption of eID tokens. In Belgium, for instance, more than 600 services can be used online with the eID card. In the Nordic countries, not only the Government, but also the private sector is allowed to issue eIDs (e.g. the BankID – initiative of banking institutions, the PKI MobileID – brought to customers by telecom operators alone or in collaboration with banks). Those Governmental eID schemes that allowed for a great variety of (public and private) services proved to be more successful, not only because they saved citizens’ time and money, but also because they influenced an increased eID use.

eID tokens should be easy to use. Installing (and keeping up-to-date) pieces of software, card reader drivers and root certificates (for signature verifying purposes) on one’s computer can be perceived as being cumbersome and solutions that circumvent these steps ought to be preferred. From this point of view, username-password combinations and OTP solutions are more user-friendly than PKI or attribute-based smart cards; they may be preferred in spite of having a lower degree of security.

Authentication ‘on the go’ is currently possible in the countries that introduced Mobile eIDs, but digitally signing documents seems to be dependent on installing additional software on the user’s PC. If further developments would allow digital signatures to be added to documents by using the (smart) phone only, a greater penetration of Mobile eID solutions can be expected. Even in the case of password-based solutions, the management of OTP lists (from a user’s point of view) can be troublesome. In order to replace the printed lists of passwords, The Danish NemID scheme introduced in November 2012 an OTP generating USB token.

Perceived usefulness

It is important that the eID solution has clear benefits, which are also communicated in a clear manner to the public. From the citizen’s point a view, an eID solution is perceived to be useful if it either saves money / time (for instance, by conducting transactions with the Government online from home, instead of having to go to public authority offices) or it brings another type of convenience to the user. However, in the first motivation, online authentication / digital signing is appreciated only in relation with the services that are being offered to the card holders. The more (public and private) services are available, the higher the level of perceived usefulness is. The second motivation of increasing the perceived usefulness is exemplified by the case of Portugal, where the national eID card combines five previous cards into one (ID card, tax card, social security card, voting card and social services card), making it more convenient to 5/8 6/8 authenticate to the various service providers.

Availability of other solutions

In many European countries, multiple (types of) eID solutions are available in parallel. The challenge remains to convince the citizens to use the newer, more secure ones, not necessarily those they are used to. Finland, for instance, was the first European country to introduce PKI cards (national eID cards – FINeID) in 1999. However, ten years later, only 300.000 citizens (out of 5 million in total) applied for the cards. The reasons are multiple: not only that the FINeID card is not mandatory, but it appears that the bank-authentication method (printed OTPs) was better known and, therefore, more employed in the online environment, even for non-banking services.

The switching costs associated with a new eID solution refer to both the price the user has to pay for the access rights, token and equipment of the eID functionality and the time spent in learning to use the new technology. The price paid for an eID token becomes a factor only in the case where other solutions are available. The time spent in learning influences the adoption rate of an eID solution especially when there is an important technological gap between what is employed currently and what was used before.

For all solutions being studied, the availability of services was an important factor that influences the eID adoption rates. The convenience and the simplicity of the solution should also be taken into consideration. For the purpose of simplifying an eID scheme, several implementations of mobile PKIs with the private key being stored on the SIM card and PKI ‘plug&play’ tokens were introduced. They proved to be more convenient than usual smart cards, because they save the users from the burden of installing a card reader, subsequent drivers and software. However, for a Mobile PKI SIM solution to work, a high level of trust must exist between the parties involved in developing the scheme: usually – the Government and MNOs. In the next five to ten years, it is expected that eID schemes will be implemented also in Eastern and Southern Europe. The countries that have recently implemented national IDs on smart cards that store biometrics, but lack the eID functionality, could choose to offer eID services on bank cards (as in the case of Iceland and Austria), on other types of cards (profession- related, tax cards etc.) or on tokens.

Nevertheless, it is also expected that initiators of eID solutions will look into increasing the privacy of the eID bearer – either through Attribute Based Credentials or other solutions (e.g. PKI solutions with multiple certificates and citizen numbers in order to decrease the possibility of information coupling between different service providers).