An in-depth study on the potential to pool ID documents to reap considerable benefits such as a greater capacity to modernize IDs of all kinds at minimal cost and provide stakeholders with a strong identification platform with consistent security and trust

by Francisco Alcalde, Gemalto

Above all, the e-Government approach is a unifying and progressive one. While each central or local administration can move forward at its own pace, the e-Government program itself must strive to combine these initiatives into a cohesive whole, while generating savings by pooling resources. For secure ID documents, there is a threefold challenge to ensure they are long-lasting, adaptable and unifying.

This new challenge for ID documents will be all the more acute as more services become reliant on them, and especially with a move to pooling, where several administrations may be working with the same document. At this point the trust factor will extend into territories outside the conventional issuer / user relationship. These factors clearly point to considerable constraints in terms of security and durability.

If ID documents can be pooled, so can the infrastructures, processes and services linked to them; from the registration and issuance phase, through to verification and post-issuance.

Pooling new documents and infrastructures will provide considerable savings in terms of processing costs and cutting the potential sources of non-quality in back offices.

Pooling provides a greater capacity to modernize all or part of identity, travel, health or even driving license documents at minimal cost, and to improve and develop online public services. Providing public and private stakeholders with a strong identification platform and providing a consistent level of security and trust will also foster the development of third-party services based on this pooled architecture. This trend will contribute to the underlying economic dynamic.

The organizations in charge will therefore need to implement technical and organizational solutions which promote this pooling approach. They will be faced with some challenges – in implementing a multi-application platform; in terms of scalability and adaptability of this platform, in particular the need to upgrade applications and data in the field after cards have already been deployed (post-issuance processes or add new); and in terms of security, confidentiality and even trust between issuing bodies, and the constraints in choosing a multi-issuer structure.

On the strength of its experience in deploying more than 80 governmental programs, Gemalto makes three recommendations:

- break down barriers and encourage initiatives towards pooling of documents at national level. Fragmented infrastructures with several different ID documents do not lend themselves, in the long-term, to the creation of a trusted national infrastructure able to support the requirements of e-ID, which is an essential vehicle for the modernization and digital development of a country

- do not wait to reach critical mass before launching the initiative. The initiative will grow as the concrete benefits become apparent, even if they are small to begin with, since the first areas of application are naturally limited in scope during the start-up phase

- invest now in solutions that are at once totally flexible, confidence-inspiring and collaborative. Select a solution that secures the multi-application multi-issuance environment and the post-issuance capabilities. Having clear ideas about the program from the outset will give the project real potential for success.

e-Government programs constraints

Many states have begun e-Government programs with the design, production or deployment of secure e-ID cards, often at the initiative of the interior ministry. Too often, the process has been approached from a technological standpoint, and many advanced countries are now attempting to demonstrate that, beyond the security benefits for both states and individuals, e-ID can provide citizens and businesses with real services and benefits, without infringing upon new rules on data protection and civil liberties. This also makes it easier to garner the political support required to deploy these very costly projects.

Many states have begun e-Government programs with the design, production or deployment of secure e-ID cards, often at the initiative of the interior ministry. Too often, the process has been approached from a technological standpoint, and many advanced countries are now attempting to demonstrate that, beyond the security benefits for both states and individuals, e-ID can provide citizens and businesses with real services and benefits, without infringing upon new rules on data protection and civil liberties. This also makes it easier to garner the political support required to deploy these very costly projects.

Another challenge, particularly during these times of ‘economic crisis’, is to demonstrate that the e-Gov 2.0 approach and the associated use of smart cards yield a good return on investment, if not financially then at least politically. Many states and local authorities are attracted by the versatility of these electronic ID documents and encourage their use in multiple everyday activities (transport, access to public buildings, payment for public services, etc.). Within this context, the technical structure in place must be unifying.

But the scale of this undertaking means that simultaneous implementation is not possible, since each ministry, each administrative body moves at its own pace. Out of all government departments, finance ministries are the most comfortable with the notion of modernizing in order to gain a higher return on investment. Education, legal and defense ministries often do not have the budgetary resources for an in-depth transformation. Social services and welfare systems yield the most obvious return on investment in political terms, and can allow considerable savings to be made at a time when welfare systems are at breaking point. Local initiatives often progress at a faster rate than national programs, and can be useful testing grounds.

It is therefore essential to ensure that each area of e-Government construction progresses at its own pace, according to its ability to adapt to the new rules, adopt modern digital tools and launch its own services.

Planning stages

The introduction of an e-Government program is a major political decision, involving all administrative bodies and resulting in a far-reaching cultural transformation in service relations practices between public service providers and users. This approach may continue over several years, so the different stages need to move forward in step, and trial projects should be launched, demonstrating the political will, potential for results and benefits generated by the program.

The introduction of an e-Government program is a major political decision, involving all administrative bodies and resulting in a far-reaching cultural transformation in service relations practices between public service providers and users. This approach may continue over several years, so the different stages need to move forward in step, and trial projects should be launched, demonstrating the political will, potential for results and benefits generated by the program.

Governments most often adopt a four-stage approach to achieve the development objectives mentioned above. This involves:

- the creation of an environment of trust for essential digital exchanges in the country.

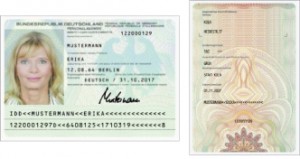

- providing secure ID documents based on a reliable civil register, to offer every individual access to each of the state’s modernized services, to promote national and international mobility, with a view to protecting citizens’ identity and to fight fraud and cybercrime. Secure documents also help countries participate in international cooperation with regards to the regulation of migration. They are also the first tangible result from the transformation program.

- launching the first online services – an ID document without application services can be likened to a motorway without traffic and exits. That is why the first use assigned to these documents is access to online services, linked to the ministries providing the funding for these initial investments; this means that they are often public services (online taxes, online police services, etc.).

- unifying and launching services in the social, economic, health and education sectors – this policy includes the creation of local services and citizen welcome centers to provide local support during this modernization process to regions and individuals for all areas of everyday life.

But which services should be pooled? The new generation of national ID cards (with microprocessors) therefore has a unifying role on two fronts.

Firstly, multi-service, where the card can have several different uses, both in the physical world and the digital world. It can be used as an identity card, driving license, health insurance card, poll card, public transport card, etc. It can also be used for identification, either face-to-face with a policeman, or over the internet on the government’s web portal, or even for private services.

Secondly, multi-operator, where the card is issued by one of the public authorities driving the e-Government program, but its electronic components can be updated or loaded with new applications by other public or private stakeholders (other ministry, region, town, bank, transport operator).

Pooling infrastructures

The cost of a smart card project within a governmental context can be broken down in a similar way to an ID card, health insurance card, or driving license project.

The main components are the cost of the infrastructure to register the data of citizens, to record their administrative data and potentially their biometric data (photos, fingerprints); the cost of the infrastructure to issue documents and secure cards, in general from a central site for optimization reasons; the cost of the infrastructure to check documents, with the infrastructure of readers in the various government locations, municipal buildings, town halls, prefectures, etc. This infrastructure is also used after documents have been issued, when the data in the chip needs to be updated; and of course the cost of the card, taking into account the technological choice (contact card such as a bank card, or a contactless card, such as an electronic passport or transport card, or a card which combines both types of technology). In the case of multi-application cards, the issuing and verification components play a significant role, since they enable post-issuance services, such as adding to or updating data in the microchip throughout its entire lifecycle. So the data in the card is not fixed, but on the contrary changes in step with the life of the citizen (change of civil status, change of address, addition of other services in the card, updating security certificates, etc.).

The main components are the cost of the infrastructure to register the data of citizens, to record their administrative data and potentially their biometric data (photos, fingerprints); the cost of the infrastructure to issue documents and secure cards, in general from a central site for optimization reasons; the cost of the infrastructure to check documents, with the infrastructure of readers in the various government locations, municipal buildings, town halls, prefectures, etc. This infrastructure is also used after documents have been issued, when the data in the chip needs to be updated; and of course the cost of the card, taking into account the technological choice (contact card such as a bank card, or a contactless card, such as an electronic passport or transport card, or a card which combines both types of technology). In the case of multi-application cards, the issuing and verification components play a significant role, since they enable post-issuance services, such as adding to or updating data in the microchip throughout its entire lifecycle. So the data in the card is not fixed, but on the contrary changes in step with the life of the citizen (change of civil status, change of address, addition of other services in the card, updating security certificates, etc.).

Three cross-functional factors ensure secure ID cards are issued without problems – security, which is essential to the credibility of the ID document, consistency, ensuring the quality of documents and their use and an organization with management, operation, security and quality departments backed up by selected, qualified and experienced human resources.

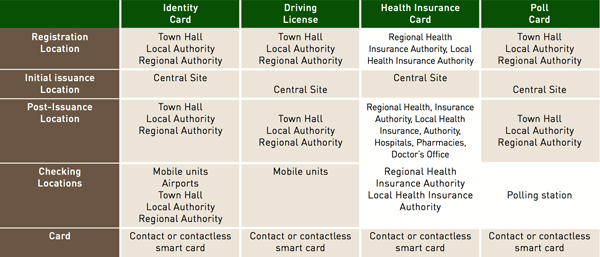

Therefore, the pooling of technology, systems, processes and organizations optimizes the implementation of secure document projects. Implementation schedules are also optimized: current status, definition of extensions and integration of changes. Risk management is improved thanks to the use of a proven architecture, and the immediate availability of a backup system. These components are identical from a technical standpoint for most governmental projects implementing smart cards. Only the actual implementation differs. Table 1 outlines the different areas affected by the pooling of infrastructures.

Overall architecture

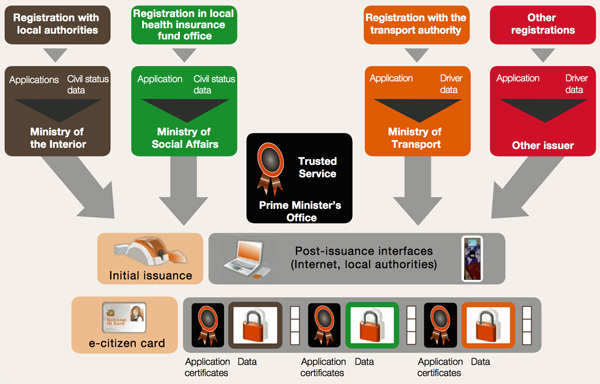

A multi-issuer pooled system for citizen cards is represented in Figure 1. It includes a central Trusted Service, used by the various issuers and operated by a cross-ministerial body – the Prime Minister’s Office, for example. This trusted service enables the various governmental bodies to issue their associated data and applications on the card in a secure and independent manner.

The initial issuance includes a phase to customize the graphics and electronics of the document with the demographic and biometric data of the user, generally provided by the Ministry of the Interior, based on civil registry data collected at local and regional level. Individuals can upload data and customize data for applications in a coordinated manner, through post issuance services such as self-service booths in municipalities, or even from personal computers connected to the internet and authenticated by the citizen card.

Registration

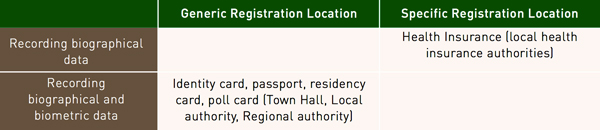

Registration is carried out differently depending on the application, so each ministry keeps their own registration methods and infrastructure. Registrations need to be classified into several categories, depending on the location and type of information to record. Table 2 sums up the most common scenarios.

Town halls or regional authorities host citizen registration infrastructures for ID card, while local health insurance authorities host the infrastructure for healthcare cards. This set-up is also possible for registration locations, in particular for ID cards and driving licenses. It would be possible to consider pooling registration systems for health insurance cards. In this respect, pooling would be of interest when it comes to taking pictures of users and taking their fingerprints, since the electronic devices required for this are costly.

The costs to acquire and operate equipment could therefore be shared. If the same public service employee could collect data for several governmental agencies, then money could be saved during operations. The solution chosen must win the trust of users, and take into account the overall security of the project. Therefore, the Ministry of Transport should only be able to add data relating to the transport application, without being able to access data relating to identity or health insurance.

If registration services were to be pooled, it would be both possible and advisable to adopt high security standards. This would provide higher assurance in the applicants’ identity and ensure the resulting document is handed out to its rightful owner. Higher levels of assurance could be achieved with face-to-face registration, presentation of several documents, secure capture and processing of biometric data, etc.

Issuing documents

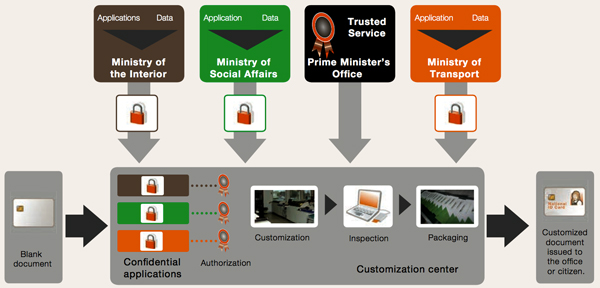

Resources can also be pooled to issue documents. Indeed, this operation includes a data processing center and a card production facility; these components are part of all smart card projects. The issuance of secure documents (or ID cards) is based on a set of consistent principles, whatever the type of document in question (national ID card, social security card, passport or driving license). An individual ID card needs to be provided in a secure manner to citizens, in line with requirements which can change over time. For a multi-issuer project, the various issuers are in charge of receiving citizen information. They each process their data in order to deliver customized applications to the personalization center, with data that is confidential, since it is encrypted with their own encryption systems.

The personalization center is a secure center, both physically and digitally. It houses customization machines. The customization, inspection and packaging phases described above take place in this personalization center. Blank documents and the various confidential applications from issuers are required for the customization process. The confidentiality and security of a multi-issuer document customization system relies on a trusted third party service. This trusted service is at the heart of the issuing process, and cements the partnership between application issuers and personalization centers.

This highly secure trusted service is generally under the aegis of a cross-ministerial organization (under the Prime Minister), or reporting directly to the Ministry of the Interior. Figure 2 is a diagram of a potential customization process. One of the advantages of this set-up is that it provides a shared document customization infrastructure. Indeed, only one personalization center is needed to customize documents, whatever the issuer of the application and its nature (transport, health, driving license, etc.). Furthermore, the independence of application issuers is ensured, since each issuer is in charge of processing its own data and possesses its own encryption systems. Finally, in addition to issuer independence, data confidentiality and integrity is ensured by encryption and signature systems for applications, which issuers provide to the personalization center. This center will then be able to decrypt and check the data thanks to the trusted third party service.

Constraints for secure IDs

The first task of a secure document is to gain people’s trust in the information or services which it hosts. This task will be difficult since services will rely on these documents, especially since pooling resources will entail several different bodies dealing with the same documents. The aspect of trust will thus take on a new aspect, surpassing the context of a classic issuer / user relationship. Naturally, this heightened trust will lead to the need for a document making no concessions in terms of security.

Demonstrable security

Inevitably, people’s trust in pooled documents will be won through an independent, recognized assessment of the security of the document. Since this assessment directly reduces the overall risks of the project, the lightweight methods that a single issuer could perhaps fall back on as part of its own program are no longer possible within a program involving several third parties.

Long-lasting security

The durability of security features is also key to gaining people’s trust. Whether to comply with regulations in force or reduce the risks of fraud, particular attention should be paid to the strength of the encryption features of these products. Security authorities cast a critical eye over the key security mechanisms in authentication or signature services, and often issue recommendations concerning the use this or that algorithm, and the estimated lifetime of protection features.

Complete and long-lasting integrity

Documents need to stand alone for their entire validity period. However, they must also display information required for a number of uses. Managing this limited amount of space, both in terms of the physical surface area of the document and the available memory in the microchip, will not only introduce the need for increased coordination between governmental stakeholders, but will also highlight the scalability offered by electronic use.

Indeed, a microchip has the advantage that it can be updated several times, while preserving the integrity of each application, or even each set of data in the chip. In order to fit in with the pooling approach, documents need to be able to adapt to all types of administrative uses, and therefore must contain advanced functional capacities. Particular attention should be paid to the communication interface (a decisive factor for the document reading infrastructure), the applications platform for the card (conditioning the potential usefulness for citizens, as well as the implementation timeframes and risks for organizations), as well as the management features of the operating system (essential for the optimum use of the document’s electronic resources).

Adapted communication interface

All electronic documents require an infrastructure of readers, which will vary depending on planned uses. Most uses rely on two types of communication: contact communication, the most widespread and tried and tested, which requires the document to be inserted into a reader, or contactless communication, enabling the document to be read from a short distance.

These types of communication should be considered in the following cases. Contact cards will be mainly used for health insurance and applications over the internet (e-Government); contactless cards can be used within some infrastructures for identity checks (at border crossings for example), public transport, or payment in university cafeterias; driving licenses can be designed to be checked either using a contact or contactless interface.

A range of governmental applications

Governments can take full advantage of the electronic features of documents by using applications in the card which can link up with issuance and checking infrastructures. These applications are often essential to ensure projects run smoothly. They need to ensure they comply with standards and regulations (ICAO, EU, ISO/IEC, etc.), combine security, performance and compactness while integrating with various systems, with the major constraint for any embedded system deployed nationwide: requiring as little maintenance as possible in the field.

Astute management of memory

In order to ensure there are sufficient resources for the applications of all bodies, particular attention should be paid to the issue of the total available memory in documents. This resource cannot be increased once the document has been issued, and has a considerable effect on costs. Therefore, prior consultation and research should be carried out by organizations, in order to not only choose the best size for their project, but also to implement the technical means to avoid the duplication of information in the document. Our recommendation would be to provide enough space for the storage of data to identify the cardholder (photograph, name, address, civil status, fingerprints), and three digital certificates. In this case, a minimum of 72 kB is required, especially if the document will also be used as a travel document, according to the ICAO standards.

A longer lifecycle

Pooling introduces the need for the effective management of the lifecycle of documents, including updating or upgrading them in the field. Indeed, in contrast to traditional secure document, which is issued just once by a single body, a pooled document will need to be altered by various bodies (organizations) at various stages. This means that after being issued, certain tasks still need to be performed in an effective and secure manner. Verification and post-issuance component can be pooled to a certain extent. First of all, it should be noted that all these cards are not checked and updated at the same rate. A health insurance card for example will probably be checked more often (when used with healthcare professionals or in social security agencies) than a driving license.

Post-issuance requirements vary depending on the type of document:

- National ID Card: except a change of address or a renewal of an essential certificate for digital signatures (every two to three years), ID cards are not frequently updated. In some cases (name change following a marriage), a new card will be issued

- Driving License: in general, these are updated relatively infrequently because of the regulations in force, in particular the requirement to visibly display the types of vehicles which the holder is authorized to drive on the card. For the implementation of a points system or fines, updates could be more frequent, and would mainly rely on a system involving mobile terminals

- Health Insurance Card: this is probably the most frequently updated card. Therefore, depending on the case, insurance entitlements are updated each quarter or year. The list of beneficiaries could also require more frequent updates

- Poll card: in general, this card is updated for each election, to include the polling station where the holder is registered to vote, and a stamp attesting that the holder voted. Furthermore, the post-issuance location varies greatly depending on the application. From a technical standpoint, the infrastructure is the same whatever the application, but requires the user management systems for each application to be networked (the national database of driving licenses, health insurance database, etc.) and a link to the PKI (for the renewal of certificates). In a multi-application approach, the equipment for this can be shared, even if the locations are different. It is therefore possible to pool the verification and post issuance infrastructure according to a geographical factor; the updating location. Therefore, all cards issued by the government (national ID card, driving license, or even health insurance card), could use the same infrastructure.

Eventually, it will be possible to push this approach further, offering self-service booths where users can update several different types of cards. Connecting systems together also makes issuing new cards easier, in the event of theft or loss. All data and applications could be reloaded onto the new card in one fell swoop.

Deployment and recommendations

In addition to economies of scale, reducing the number of documents to be carried by citizens, and the number of production, registration and issuance procedures, pooling speeds up the deployment of new services for existing members or newcomers. It provides organizations with access to resources, which they could not access previously. It eliminates barriers to entry, which have been impeding certain organizations because of issues relating to equipment, resources and scale: local and regional authorities or other public or semi-public organizations. Pooling improves the quality of pooled documents and services due to the organizational or even contractual requirements inherent to this approach. It also promotes the improvement of the services offered to citizens.

Pooling new secure documents and their infrastructures, in addition to economies of scale, cutting costs and appeasing citizens’ practical concerns, aims to facilitate and speed up the deployment of e-services and the emergence of a digital society. The challenge is to improve the deployment of remote services while ensuring citizens take up these services. This change must enable public services to join the ranks of the best services in the private sphere, such as in the insurance, banking, or financial sectors. Pooling secure documents and their infrastructures will then help to promote national economic growth. The organizations in charge therefore need to implement technical and organizational solutions which promote this pooling approach.