Robert A. Mocny is the Director of the United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT) Program. US-VISIT is part of the National Protection and Programs Directorate at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. US VISIT provides identity management services – the collection, analysis, and storage of biometric and associated biographic data – to decision makers in Federal, State, and local law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Prior to his current responsibilities, Robert Mocny served in senior positions at the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), including as Director of the Entry/Exit Project, acting Assistant Commissioner for Inspections, and Special Assistant to the Deputy Commissioner. While at INS, he led an interagency project team that established the Secure Electronic Network for Traveler’s Rapid Inspection (SENTRI) Program.

An overview of the development and deployment of biometrics in the US-VISIT program for identifying who may or may not enter the country

US-VISIT’s use of biometrics is helping to make travel simple, easy and convenient for legitimate visitors, but virtually impossible for those who wish to do harm or violate U.S. laws. Biometrics collected by US-VISIT in various forms and linked to specific biographic information enable a person’s identity to be established, then verified, by the U.S. government. With each encounter, from applying for a visa to seeking immigration benefits to entering the United States, US-VISIT has helped stop thousands of people who were ineligible to enter the United States. ID People spoke to Robert A. Mocny, Director of the US-VISIT Program on the deployment of biometrics – past, present and future – and how the program and the technology in particular, help prevent identity fraud and deprive criminals and immigration violators of the ability to cross borders.

US-VISIT’s use of biometrics is helping to make travel simple, easy and convenient for legitimate visitors, but virtually impossible for those who wish to do harm or violate U.S. laws. Biometrics collected by US-VISIT in various forms and linked to specific biographic information enable a person’s identity to be established, then verified, by the U.S. government. With each encounter, from applying for a visa to seeking immigration benefits to entering the United States, US-VISIT has helped stop thousands of people who were ineligible to enter the United States. ID People spoke to Robert A. Mocny, Director of the US-VISIT Program on the deployment of biometrics – past, present and future – and how the program and the technology in particular, help prevent identity fraud and deprive criminals and immigration violators of the ability to cross borders.

What is the premise behind the establishment of the US-VISIT program?

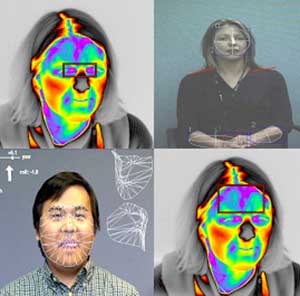

The main premise behind the US-VISIT program is determining the accurate identification of foreign nationals traveling to the United States. One of the first responsibilities of Government officials who grant visas, admit foreign nationals, and provide a benefit, is to ascertain who it is they are dealing with. They are trying to determine, ‘Who are you?’ They need to verify that you are who you purport to be. Traditionally, we have done that with passports, and other Government-issued credentials. But in all cases there is some attempt to verify one’s identity. Comparing your face to a photo is one way to do that. Using biometrics is a much more certain way of determining and protecting identity and securing travel documents.

Since US-VISIT was established in 2004, we have become the single source identity-screening service provider for the Department of Homeland Security and our services have strengthened immigration and border security to unprecedented levels.

From a technology viewpoint, how have developments in biometrics boosted the services you provide and what specific combinations are deployed in terms of matching and system interoperability?

This is where the biometrics industry deserves great credit. I mean, biometrics have been around for quite some time. We have been fingerprinting people for thousands of years. We have been studying facial and speech recognition for decades. But we have not been able to deploy large-scale biometric systems into an operational environment that requires fast transactions but little or no margin for error. With the advent of US-VISIT, we can now do this – and quite successfully. And the ‘we’ is the United Kingdom, Japan, the European Union, and many other countries around the world, and the number continues to grow. India can now give every one of its citizens who want a known identity a national identification card that provides access to services.

This is where the biometrics industry deserves great credit. I mean, biometrics have been around for quite some time. We have been fingerprinting people for thousands of years. We have been studying facial and speech recognition for decades. But we have not been able to deploy large-scale biometric systems into an operational environment that requires fast transactions but little or no margin for error. With the advent of US-VISIT, we can now do this – and quite successfully. And the ‘we’ is the United Kingdom, Japan, the European Union, and many other countries around the world, and the number continues to grow. India can now give every one of its citizens who want a known identity a national identification card that provides access to services.

These advancements in the biometrics industry will also allow for more automated border crossing systems, which will reduce the cost of maintaining immigration controls, enhance border security, and spur the global movement of tourists and people engaged in international business.

What live examples demonstrate successful results with respect to homeland security in the United States and elsewhere?

There are literally thousands of cases that would prove the point that the global implementation of biometrics has been a success. Here is one notable example that illustrates the partnership between the United States and its Five Country Conference partners – Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom: an Australian citizen, who was originally from Somalia, rapes a 13-year-old girl. He is arrested and released pending trial. He then flees Australia. Through a combined effort with Australia, the United Kingdom, and our own US-VISIT Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT), he is located in the United Kingdom, where he has been granted refugee status under an assumed name. He is ultimately arrested and is now back in Australia serving his time in prison.

There are literally thousands of cases that would prove the point that the global implementation of biometrics has been a success. Here is one notable example that illustrates the partnership between the United States and its Five Country Conference partners – Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom: an Australian citizen, who was originally from Somalia, rapes a 13-year-old girl. He is arrested and released pending trial. He then flees Australia. Through a combined effort with Australia, the United Kingdom, and our own US-VISIT Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT), he is located in the United Kingdom, where he has been granted refugee status under an assumed name. He is ultimately arrested and is now back in Australia serving his time in prison.

Which identification systems are in place through the program and how do they operate in terms of controlling who arrives and leaves the country?

US-VISIT currently uses fingerprints as the only automated means by which we identify people upon entry into the United States. We’ve been testing and piloting other biometric modalities such as iris scans and facial recognition to determine their potential for implementation in an operational environment. Upon exit, we still do it the old-fashioned way – biographically – although we now have an automated vetting and enhanced biographic exit capability. But the Department of Homeland Security is committed to deploying a cost-effective biometric system for exit in the next several years.

Collaboration and data sharing is essential to verify a person is who they purport to be. How is information shared on a cross-agency basis both within the U.S. Government and with international organizations such as INTERPOL?

Here again we see the power of biometrics and the terrific cooperation we have with

the Department of State, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, our international partners, and yes, INTERPOL.

Here is one classic example from several years ago that I like to reference because it highlights what we have achieved together: a Costa Rican national goes to the U.S. Embassy in San Jo

se, Costa Rica. He applies for a visa, has his fingerprints taken as part of the new process – and this was when we were taking just the two index fingers, now we take all 10. In any event, he clears the checks, is given a visa, and heads back home to get ready to fly to the United States.

But subsequent to his visit to the embassy and before he gets on the plane, we receive a new batch of fingerprints from INTERPOL. We have a process called wrapback which allows us to inject new fingerprints into IDENT and run those prints against all of our holdings to determine if we have seen this person before. In this case, we had. The Costa Rican was actually a Bulgarian national who had absconded with €10,0000 a decade before. He was called back to the embassy on a ruse, arrested, and ultimately extradited back to Bulgaria. Exposing this false identity would not have been possible if the Department of State had not deployed its biometric visa process, which uses our database to store the prints.

What international protocols are in place under the program for data exchange on illegal or criminal individuals and how effective are they?

Primarily we operate internationally by signing memorandums of understanding with other countries. But we also have such agreements between departments within the United States and we have existing information exchange protocols with INTERPOL.

We may also issue letters of intent. The whole point is to document the use of biometrics, which preserves the integrity of the data, protects the privacy and rights of an individual’s personal identity information, and basically lets us operate in a legal framework.

In this regard, how important is privacy and what safeguards are in place to ensure data is protected, particularly in the digital age when vast amounts of sensitive and sometimes unmanaged information is potentially at risk?

I would like to make a strong point here. We take privacy very seriously at US-VISIT. From the inception of the program, literally the day after Secretary Tom Ridge announced to the public that we would design the entry-exit system with biometrics, I noted in my diary that we would need to prepare a briefing for privacy advocates. We have a dedicated team of privacy professionals whose day-to-day job is to publish documents that keep the public aware of our activities through a transparent process.

We issue Privacy Impact Assessments and post them on our Website for all to download and read. We dedicate an entire week each year to privacy education for our employees, where we hold sessions with guest speakers who are privacy advocates themselves. Through a variety of entertaining activities, we even inject some fun into ways in which we, as a program and individually, can practice better privacy behavior.

In the field of serious crime and anti-terrorism, what role does US-VISIT play on the global stage in terms of cooperation and prevention?

A rather large one. Through our excellent relationship with the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division, we have established full interoperability with their fingerprinting system. On any given day, we receive thousands of fingerprints of people wanted for crimes committed in the United States, known and suspected terrorists, and international fugitives wanted by INTERPOL.

A rather large one. Through our excellent relationship with the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division, we have established full interoperability with their fingerprinting system. On any given day, we receive thousands of fingerprints of people wanted for crimes committed in the United States, known and suspected terrorists, and international fugitives wanted by INTERPOL.

We support the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Secure Communities program through which anyone who is arrested for a crime – in a growing number of jurisdictions in the United States – is automatically checked against our data to see if they are in the country illegally and may be subject to removal. And through our data sharing partnerships with an increasing number of international police and immigration authorities, we are identifying criminals and terrorists worldwide.

As far as this international cooperation is concerned, are there regions or nations which are less technologically-advanced in their systems today? If so, does US-VISIT work with these countries to develop modern solutions to further the cause of global security?

Absolutely. We believe we have an obligation to do so. At US-VISIT, we have an office dedicated to this effort – the Information Sharing and Technical Assistance branch. These women and men reach out across the globe to make sure countries and international organizations that are considering adding biometrics to their immigration and border management processes have the information they need to successfully deploy their systems. Whether it is a list of international standards that they should consider adopting, a request for proposal review, or actual on-the-ground technical assistance by a US VISIT employee, we stand ready to share our experiences and lessons learned along the way.

As innovations in biometrics continue to emerge, with many border control points – particularly airports – deploying facial and iris recognition at e-gates, what progress has been made in the realm of standards and specifications both for new technologies and the end product (an ePassport)?

Significant progress has been made in using alternative biometrics for identity purposes. The current facial image of visa applicants captured at U.S. Consulates can now be verified through improvements in the standards used to capture, store, and transmit developed by the American National Standards Institute and the National Institute of Standards and Technology. US-VISIT contributed to these efforts by researching and testing new technologies and developing standards for quality that support operational needs.

As a result of this work, more countries are issuing electronic passports and using them for facilitated, automated border control. Just one recent example is the plan for Australia to allow access by U.S. ePassport holders to its SmartGates upon arrival in Australia. Another example is the standard developed to allow an iris image to be placed on an electronic chip. These entirely new specifications were created to fill an operational need. Iris images are smaller than fingerprint or facial images and are highly accurate and reliable. Iris collection is non-invasive and does not have the stigma associated with fingerprints, but is an important a tool for security.

This means that iris images can be collected and stored in chips for use to gain access to buildings and systems. The International Civil Aviation Organization Document 9303 specifies iris image capture and storage in Machine Readable Travel Documents. US-VISIT contributed to the development of this standard and its specifications and the Department of Homeland Security is working towards implementing technology meeting these standards.