Dr. Gérald Santucci is Head of the Unit Networked Enterprise & Radio Frequency Identification at the European Commission. Work underway includes the monitoring of the EC Recommendation on the implementation of privacy and data protection principles in RFID-enabled applications, with special emphasis on privacy and data protection impact assessments and on signage, the EC Communication on the Internet of Things. Gérald Santucci is also the acting chairman of the Expert Group on the IoT, composed of about 50 stakeholders from law, economics and technology, which advises the EC on Internet of Things evolution and associated public policy challenges. He is highly committed to develop cooperation with Europe’s international partners to promote the exchange of information and the definition of global standards and regulations in the emerging field of Internet of Things.

A view on combining the necessities of identification, innovation and in security in a broader common perspective: the Internet of Things is to transcend the short-term opposition between social innovation and security by finding a way to combine these two necessities

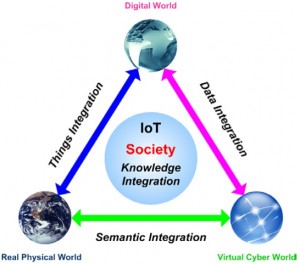

The Internet, the World Wide Web or www. – is 20 years old. Over the past two decades the world has seen disruptive innovations that have impact the web’s content in terms of security, connectivity and data management. This phenomenon is now compounded by the rapid rise of the digital world in terms of object to object communications. This has in recent years given rise to the concept of the Internet of Things. ID People spoke to one of the IoT’s leading lights, Dr. Gérald Santucci is Head of the Unit Networked Enterprise & Radio Frequency Identification at the European Commission, to ascertain the role played by identification in this entire arena and how necessary policies and governance are in a world where the physical and virtual interconnect.

The Internet, the World Wide Web or www. – is 20 years old. Over the past two decades the world has seen disruptive innovations that have impact the web’s content in terms of security, connectivity and data management. This phenomenon is now compounded by the rapid rise of the digital world in terms of object to object communications. This has in recent years given rise to the concept of the Internet of Things. ID People spoke to one of the IoT’s leading lights, Dr. Gérald Santucci is Head of the Unit Networked Enterprise & Radio Frequency Identification at the European Commission, to ascertain the role played by identification in this entire arena and how necessary policies and governance are in a world where the physical and virtual interconnect.

How crucial is identification in the context of the Internet of Things?

The Internet of Things envisions billions of devices of our daily lives interconnected in such a way that applications that were not possible in isolation emerge from the combination of capabilities and the cooperation of such smart objects. In such a vast network of interconnected objects, the issue of identification of a particular object and its addressing mechanism play a crucial role that affects all other aspects of the system, including its overall architecture, privacy characteristics, and governance.

It is feasible in practice today to provide in an efficient way a unique ID to arbitrarily small devices. However the issues of providing non-colliding unique addresses in a global scheme requires an infrastructure that supports highly dynamic devices that appear and disappear from the network at any time, move seamlessly between different local and/or private networks and have the flexibility to either identify its user uniquely or hide her identity, thus preserving her privacy as needed.

Is there a disparity between unique addresses on a network and the actual ID of the object or device supported by the address?

Yes, there exists a conceptual difference between the ID of an object and its network address (or addresses). In the most general case, the ID of an object and its address are distinct and serve different purposes. The former provides a unique handle to the object itself whereas the latter might change depending on the physical location of the object, its logical membership to one or several networks, or the current role of the object. Also the addressing scheme could be heterogeneous and a particular object should have the capability to “speak” different flexaddressing schemes according to the networks to which it belongs.

Yes, there exists a conceptual difference between the ID of an object and its network address (or addresses). In the most general case, the ID of an object and its address are distinct and serve different purposes. The former provides a unique handle to the object itself whereas the latter might change depending on the physical location of the object, its logical membership to one or several networks, or the current role of the object. Also the addressing scheme could be heterogeneous and a particular object should have the capability to “speak” different flexaddressing schemes according to the networks to which it belongs.

Finally, the issue of object discovery and resolution is a very important one that affects the choice of identification and addressing scheme. This is particularly true if the system is global and the issues of scalability and interoperability are crucial. Object discovery is, for example, a trivial task in small networks of several hundreds or thousands of devices; however, using the same scheme in a network of millions of devices would immediately grind the whole network to a halt.

In this regard, how do the different environments, such as mobile and centralized, be configured to cope with object discovery on multiple or changing networks?

Regarding object resolution, the assumption is the existence of a naming scheme that allows the user or another device in the system to find the object it is looking for. For the most part, the Internet uses a hierarchical naming scheme, the URLs, that is not suitable for a highly mobile environment such as the one envisioned as part of the Internet of Things.

URLs are not network location transparent, that is, to disclose information about the network where a resource – a computer – is located. This makes it extremely expensive to move between networks, where the “name of the computer” has to change when moving from one network to the next.

What are some of the specific challenges faced today?

We should look at the scale of the challenge in terms of device population with which the Internet of Things is presented. Firstly, it involves billions of smart devices in use all around the world. In 2010, estimates showed there were12.5 billion connected devices in circulation and this is expected to double by 2015 to 25 billion and reach 50 billion by 2020, according to forecasts by companies such as Cisco and Ericsson. When put in context, this staggering figure is more than seven times larger than the world’s population of 7 billion today. The identification of a particular object and its addressing mechanism is therefore critical in this age of digital interconnectivity.

We should look at the scale of the challenge in terms of device population with which the Internet of Things is presented. Firstly, it involves billions of smart devices in use all around the world. In 2010, estimates showed there were12.5 billion connected devices in circulation and this is expected to double by 2015 to 25 billion and reach 50 billion by 2020, according to forecasts by companies such as Cisco and Ericsson. When put in context, this staggering figure is more than seven times larger than the world’s population of 7 billion today. The identification of a particular object and its addressing mechanism is therefore critical in this age of digital interconnectivity.

On the issues of multiple versus unique identifiers, the question needs to be asked whether it is feasible to provide a unique identifier to arbitrarily small devices in an efficient way. Similarly, we need to clarify the distinct roles of identifiers and their network addresses, as most cases the ID of an object and its address (or addresses) are distinct and serve different purposes.

Given these hurdles that need to be overcome, what objectives and policy options could be set in order to achieve global governance that benefits industries in terms of resources, efficiencies and costs?

As far as identification policies are concerned, there exist a number of options, all with their own distinct opportunities, threats and preference levels.

As far as identification policies are concerned, there exist a number of options, all with their own distinct opportunities, threats and preference levels.

Doing nothing or, at best, selfregulation is one alternative. It means standards would be market driven and therefore perhaps a preferred route for business as global market forces would lead in directing progress.

Secondly, “soft law” could be put in place and this would specifically support some of the more sensitive industries where data protection and transparency is critical – such as national or regional large scale applications in health care. This however, would lead to market fragmentation, making future community- wide service integration more costly.

A third option is co-regulation, which would involve mandated long term objectives with local implementation scheduling. This could be an effective policy for Europe to support the single market and affirm its own values with respect to IoT evolution, but on the down side this could widen the “IoT divide” with other countries.

Lastly, if a binding law was introduced and enforced the necessary impact for data protection would be achieved, but this could limit future technological innovation as it would be bound to specific technology identified as secure and mandatory, rather than permitting choice.

It is too early to say which option is the “best”. Maybe a mix of these options will need to be considered depending on actual technology capabilities and market situations.

What role is the European Commission playing in this transitional debate?

Let me stress first that the evolution of the Internet of Things is a truly global subject. It means principles, norms, rules, and decisionmaking procedures that are shared among all sectors of society – the private sector, governments and civil society – and, as much as possible, among many countries.

Let me stress first that the evolution of the Internet of Things is a truly global subject. It means principles, norms, rules, and decisionmaking procedures that are shared among all sectors of society – the private sector, governments and civil society – and, as much as possible, among many countries.

Depending on whether usage will drive developments towards a globally unique identification scheme or several distinct ID spaces, our objective should be to identify policies that support an identification, addressing and naming scheme able to address two main challenges:

- how to give an object the capability to operate as part of different networks in cases where the ID of that object and its address are different?

- how to deal with object resolution and object discovery for finding information about an object with a specific ID?

In addition, such a scheme should fulfil a number of nonfunctional requirements such as network independence, scalability, interoperability, reliability, privacy and security, and support for user and device mobility.

As I said before, it is too early to say if the European Commission will formulate a policy in this respect. For the moment, there is consensus on the fact that the issue of identification of a particular object and its addressing mechanism will be a critical one for any network of interconnected objects. The IoT Expert Group will pursue its work until the end of this year. At the same time the European Commission consults a number of relevant regulatory bodies. A decision on how to deal with the governance of the IoT should be expected by the middle of next year.