Rob van Kranenburg is a author of The Internet of Things, a critique of ambient technology and the all-seeing network of RFID, Network Notebooks 02, Institute of Network Cultures. He is co-founder of Bricolabs, Founder of Council and co-founder of the Internet of People. He ranks 6th on the top 100 IOT thinkers list of Postscapes and is a member of the IOT EG of the European Commission, Chair of the Working Group Society of the IOT Forum and Stakeholder Coordinator for IoT-A, the European Lighthouse Integrated Project addressing the Internet-of- Things Architecture.

How the virtual and the physical world is getting connected through pervasive RFID and other technologies

The so-called ‘ambient intelligence’ arising from the permeating and near invisible network of radio frequency identification tags (RFID) in the world today, promises to create a global network of physical objects every bit as pervasive and ubiquitous as the worldwide web itself. This has been coined the Internet of Things or IoT. ID People spoke to Rob van Kranenburg, author of the Internet of Things and the founder of Council to learn his take on what impact RFID, and other systems, will have on today’s wider society.

The so-called ‘ambient intelligence’ arising from the permeating and near invisible network of radio frequency identification tags (RFID) in the world today, promises to create a global network of physical objects every bit as pervasive and ubiquitous as the worldwide web itself. This has been coined the Internet of Things or IoT. ID People spoke to Rob van Kranenburg, author of the Internet of Things and the founder of Council to learn his take on what impact RFID, and other systems, will have on today’s wider society.

How would you describe the ecology of the Internet of Things with reference to RFID and other information technologies?

A near invisible network of radio frequency identification tags (RFID) is being deployed on almost every type of consumer item. These tiny, traceable chips, which can be scanned wirelessly, are being produced in their billions and are capable of being connected to the internet in an instant. Some are already calling this controversial network the ‘internet of things’, describing it as either the ultimate convenience in supply-chain management, or the ultimate tool in our future surveillance.

A near invisible network of radio frequency identification tags (RFID) is being deployed on almost every type of consumer item. These tiny, traceable chips, which can be scanned wirelessly, are being produced in their billions and are capable of being connected to the internet in an instant. Some are already calling this controversial network the ‘internet of things’, describing it as either the ultimate convenience in supply-chain management, or the ultimate tool in our future surveillance.

Currently we can discern two main blocks of thought on the Internet of Things (IoT). The first is a reactive framework of ideas and thought that sees IoT as a layer of digital connectivity on top of existing infrastructure and things. This position sees IoT as a manageable set of convergent developments on infrastructure, services, applications and governance tools. It is assumed that, as in the transition from mainframe to Internet some business will fail and new ones will emerge, this will happen within the current governance, currency end business models. The second framework is a more proactive view of IoT as a severely disruptive convergence unmanageable with current tools, as it will change the notion of what data and what noise is from the supply chain on to ‘apps’.

The IOT is an ecology of technologies and including barcodes, qr codes, rfid, active sensors, ipv6 logical extension of the computer to the environment, and the environment as an interface. It is also seen as a seamless flow between the BAN (body area network), ambient hearing aides, t-shirts (ehealth), LAN (local area network), smart metering, home interfaces for convenience services), WAN (wide area network) such as the car (eCall) and VWAN (very wide area network) such as the ‘smart’ or ‘wise’ city, extending to e-government services.

What level of impact would this concept of total connectivity have on the future business environment?

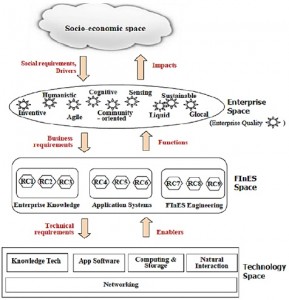

Future businesses will operate in a universal business ecosystem in which ICT will become a context for business operations spanning the whole cycle of value – from creation to consumption, encompassing both people and things, and seamlessly merging the physical world with the virtual world for the exchange of many different forms of information and the transaction of different types of value.

Future businesses will operate in a universal business ecosystem in which ICT will become a context for business operations spanning the whole cycle of value – from creation to consumption, encompassing both people and things, and seamlessly merging the physical world with the virtual world for the exchange of many different forms of information and the transaction of different types of value.

The marketplaces are likely to be radically different from those of today; the rules of engagement will be transformed to accommodate new business entities, relationships and networks; knowledge will almost certainly emerge as the premium asset and commanding currency.

The relatively future challenge is an ontological change by the hybridity of analogue and digital fostering of new entities. In the current framework we are used to dealing with three groups of actors: citizens/ endusers, industry/sme and governance/legal. These all are characterized by certain qualities, ‘a’ for citizens, ‘e’ for industry, and ‘o’ for governance. In our current models and architectures we build from and with these actors as entities in mind. The data flow of IoT will engender new entities consisting of different qualities taken from the former three groups. There will thus be no more ‘users’ who need to secure ‘privacy’ as the concept of privacy has to be distributed over the qualities of the new actor. In this conceptual space we have built notions of privacy, security, assets, risks and threats.

What does this mean for security?

The Internet of things aims at a real-time world full of connectivity of machine to machine (M2M) and machine to empeople. It favors ‘flow’. Objects can take on different roles as they can be ‘upgraded’ by digital means. Designing security in this world will be very complex. We have been used to notions of security in analogue and digital worlds. We are entering new territory when it comes to a hybrid environment, such as IoT. Security will most likely be at best very close to the object and at a point of entrance to the system.

The Internet of things aims at a real-time world full of connectivity of machine to machine (M2M) and machine to empeople. It favors ‘flow’. Objects can take on different roles as they can be ‘upgraded’ by digital means. Designing security in this world will be very complex. We have been used to notions of security in analogue and digital worlds. We are entering new territory when it comes to a hybrid environment, such as IoT. Security will most likely be at best very close to the object and at a point of entrance to the system.

Distributing security as a design principle will not take advantage of the possibilities of the new relations and serendipity. It must therefore investigate what are the primary qualities in these relationships and in order to achieve maximum effect the notion of ‘distributing insecurity’ should be investigated with programmers, engineers and data profilers. As a new ontology the IoT holds what are threats to some are opportunities to others. It is wise to go with the patterns and not against them:

Pattern 1 is on the side of decentralized, embedded, smart and connected machines/ objects,. According to Gérald Santucci, the European Commission’s IoT architect, ‘Some time in the relatively near future, the intelligence will be embedded in edge networks and devices rather than on the cloud(s). Therefore, information will no longer be confined in databases, monitor screens or smart phones of all kinds, it will reside in the objects themselves – buildings, cars, furniture, domestic appliances, clothes, bodies… Intelligence will be everywhere – around us (our environment), on us (what we wear) and in us (our body). Computers will be so small that they will become ubiquitous and invisible, thus heralding an era of smart nano-things, and they will communicate with each other and automatically connect to a huge, complex network composed of millions of invisible networks. A new paradigm is slowly but surely emerging which will impose to revisit our concepts (e.g. from privacy to privacies, from human freedom to ethics in the knowledge sphere, from homogeneous information systems to heterogeneous mediators like (ro)bots, from data subject to the empowered citizen, etc. The pattern is on the side of decentralized, embedded, smart and connected machines/objects. “

Pattern 2 is about sharing and collaboration. More social and psychological evidence that collaboration and competition are both forceful drivers of human behavior. They may be best thought of as necessary skills in a process. Stinchombe argues that in mass psychology the relationship between the idiosyncracies of an individual and the generic forces (male, education, nationality…) is 0.4- 0.6. Scaling that to one million the generic forces remain intact, yet the individual ‘power; gets cut down to 0,00004 – the rebel, the fool to the king, the terrorist, the unforeseen, the ‘suddenly’.

The internet is changing this ratio – the ratio of power – more into 0.5 – 0.5 as individuals that want to collaborate can network as professionally as industry and states. Thus the very ratio of potential acts to threats is changed and therefore ‘scale’ as a symbol for success no longer works as before: by scaling you would inevitably strengthen the 0.6. Now the scaling is horizontally. As an example of a business model, gated communities favor inclusive rent, mobility, cars, security, food…

Pattern 3 involves the integration of policy, architectural design and planning. For example, China is trying to merge deliberative democracy with a strong planning on hardware, software, legal issues, applications, services and infrastructural investments. Chinese leadership is of majority engineers. The US has no federal policy on IoT as societal innovation, only as risk/threat. That leaves the planning to the data integrator industry to work on only at a (specific) city level, not nationwide and to the social networks that will work on consumer applications, not architecture.

The EU does not make things in quantities that can dominate specs for standards, has no networks and virtually no VC. However value driven companies like Bosch and Grundfos can take the lead in terms of integration and planning. The fact that in the US and EU leadership does not comprise engineers is key. Politicians and civil servants will feel immediately threatened when confronted with losing agency or having to take on a different role. In fact their skills are highly necessary just no longer with the notion of the state.

How can today’s structures in terms of governance and standards keep pace with this level of change?

We argue that current governance structures must transform into semi-organized networks with flat and efficient properties. In doing so they must embrace disruptive technologies such as the Internet of Things. The next generation of pervasive ICT devices can play a unique role in stabilizing and balancing new societal structures. There is a need to disambiguate the productive functions in order to slow down, mediate and look for balance in the long, mid and short term with regard to bureaucracy and the democratic politics that could rendered ineffective in a ‘real-time’ world. Most centralized governance structures of today will then be replaced by every-day ICT devices that are able to participate in a societal mediation process. Globally networked and pervasively deployed, they will embed deeply into them the regulations and values of our society. They will be able to observe our behavior and adapt their behavior accordingly in order to influence our compliance to the regulations they embed. Every 5 years – or whenever appropriate – the new generations get to vote on the slider structure setting the generic fee and regulations. The settings can be tuned at regular intervals based on evaluation outcomes from empirically evidence.

We argue that current governance structures must transform into semi-organized networks with flat and efficient properties. In doing so they must embrace disruptive technologies such as the Internet of Things. The next generation of pervasive ICT devices can play a unique role in stabilizing and balancing new societal structures. There is a need to disambiguate the productive functions in order to slow down, mediate and look for balance in the long, mid and short term with regard to bureaucracy and the democratic politics that could rendered ineffective in a ‘real-time’ world. Most centralized governance structures of today will then be replaced by every-day ICT devices that are able to participate in a societal mediation process. Globally networked and pervasively deployed, they will embed deeply into them the regulations and values of our society. They will be able to observe our behavior and adapt their behavior accordingly in order to influence our compliance to the regulations they embed. Every 5 years – or whenever appropriate – the new generations get to vote on the slider structure setting the generic fee and regulations. The settings can be tuned at regular intervals based on evaluation outcomes from empirically evidence.

How plausible is this new thinking in terms of being put into practice?

We believe that our thinking is not far from reality. At a speech to the Pittsburgh Technology Council in 2009, Google’s CEO, Eric Schmidt focused on the negative effects on innovation and integration of (what he called) institutional fragmentation and wondered if governments – and the very process of policy and policymaking itself – could not benefit from the iterative cycles of measuring success and failure that characterize the engineering and design prototyping cycles. He argued that with this amount of real-time tracking, aggregated data and information – not heuristics, governing itself could benefit. In essence, particular laws can be effective for three months and evaluated, adjusted and on the basis of real data – not estimates, adjusted again. It is this process that can lead to combinatorial innovation and system Innovation.